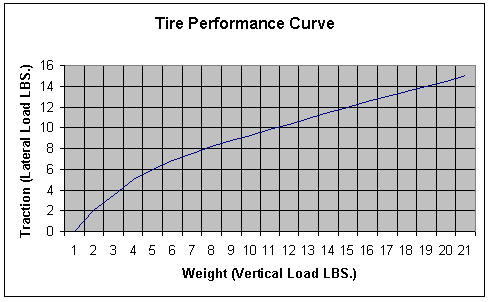

Figure 1

Input for tire performance is called "vertical load", the amount of weight placed on a tire at a given point in time. The load on a tire when the car is standing still is "Static Load" and easily measurable. The load placed on a tire when the car is accelerating, going through a turn or braking is called "Dynamic Load" and much harder to determine. By tuning the chassis or suspension components we can determine how this vertical loading will change and by knowing how the tire will respond to the change in loading, we will be able to predict the effect of the changes or performance.

"Traction" or "lateral load" is the output of a tire and represents how a tire sticks to the surface. Tire manufacturers provide data to their dealers and racing teams which tell how their tires will perform under certain conditions and loads.

To determine how a car will handle, it is important to understand how the tires translate input into output. These are the tire performance curves and show how the amount of weight (vertical load) on a tire produces a certain amount of traction (lateral load). It is important to note here that as weight increases so does traction, but increase in traction becomes less and less as weight is increased. Read that sentence again. Sounds contradictory the first time doesn't it? What it is saying is, for example, the increase in lateral load (traction) from 0-5 lbs vertical load (weight) will be greater than the increase in lateral load from 5-10 lbs vertical load. This is known as the tires "loss in cornering efficiency." A hypothetical tire performance curve is shown in Figure 1.

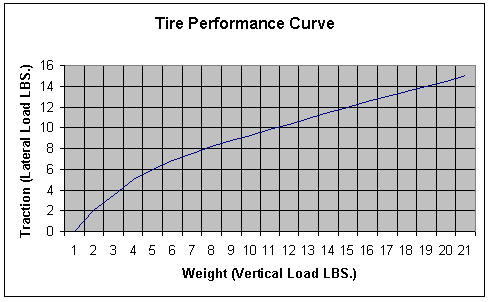

Figure 1

Cornering Efficiency (force) = Lateral Load (Traction) / Vertical Load (Weight) = 8.0 / 7.0 = 1.14

It's cornering efficiency would be 114% or 1.14 g's.

A tire will give maximum traction at a given vertical load when it is at a right angle to the ground or at "Zero Camber Angle." This produces the largest "tire contact patch." "Contact Patch" is the area of a tires surface that comes in direct contact with the road surface at any given time. A tire tilted inward at the top is known to have negative camber and a tire tilted outward at the top has positive camber. A tire with camber has a smaller contact patch and therefor less traction than a perpendicular tire. However, it is sometimes desirable to "dial-in" some camber to compensate for moving or bending of suspension parts. The ideal situation is to have just enough camber added to produce a flat contact patch where maximum traction is required, like a turn.

A tire only has a certain amount of traction at any given point in time, this is known as it's "Circle of Traction." It is dependent upon the weight on the tire, track conditions, weather, etc. This circle of traction is considered constant and is distributed between the cornering, braking or accelerating forces. If you use 25% for cornering then you have 75% to divide up for braking and acceleration.

For example, if a tire has 7.0 lbs of vertical load (weight) and it's cornering efficiency is 114%, it would provide 8.0 lbs of traction (lateral load). This 8.0 lbs is available in any direction, cornering, braking or accelerating, but not at it's full traction in any two directions at once. We see this on the track every time we race. Some guy out there, usually us, wants to accelerate (accelerating force) out of a turn faster than the tires can maintain traction (cornering force) and the result is the front and rear of the car swapping positions.

Tire and handling performance are described in terms of g-force, the amount of gravitational pull or force on an object. If an object weighs 100 lbs and we hook it to one end of a chain and the other end of the chain to a scale and rotate the object around until it weighs 200, it is said to be exposed to 2 g's of force. Now if we apply this same force to a 300 lb object it would be subjected to .33 g's and if in the same direction, it would weigh 400 lbs.

Now if we take a 30 lb. car out to a big open parking lot and draw a 200 foot radius circle on it's surface and drive that car around that circle as fast as possible and measure the time it takes to complete one lap, we can determine the lateral acceleration or cornering power in g's. A simple formula for determining lateral acceleration is:

Where:

g = gravitational force

1.225 = A constant

R = Radius of the turn in feet

T = Time in seconds for one lap

g = (1.225 X 200) / 10 ^2 = 2.45 g's

It just dawned on me that since we don't have a real performance curve, we can't figure this stuff out. Or can we. Hmmmm. Tell ya what, let's go to a nice smooth, large parking lot with our cars and the best tires, measure out a 200 foot radius circle and mark it with chalk, cones or any other object that won't be permanent (no paint is not a good idea!!!), get the old stop watch ready and run around the circle as fast as you can (No not you stupid the dang car, start the car). Got the time? Let's say our time was 14.66 seconds. Ok let's see what kind of performance we got.

Oh, by the way while we are at it, I guess some of us might want to know how fast we (the car, unless you didn't pay attention above) were going too! So......

The formula for finding the circumference of a circle is

Rate (in feet per second) is equal to Distance (in feet) / Time (in seconds)

No we still don't know our true individual tire performance, but we do know our average and that is really what makes things work. You will see that in the next segment "Weight Distribution and Vehicle Dynamics."